Every quarter we write a piece encompassing themes within our whole-person health thesis. If you would like to receive it directly in your inbox, subscribe now.

When most people hear “VO₂ max,” they picture a pro cyclist in a lab mask—yet this same metric could be the routine blood-pressure cuff of 2030. Cardiorespiratory fitness is our most powerful, neglected early-warning signal for chronic disease, and a branding problem is holding it back.

For those familiar with the term but not the science, VO₂ max refers to your body’s maximum capacity to take in oxygen, deliver it to your muscles, and convert it into energy during intense effort. Think of it as your “oxygen engine size.” The larger the engine (measured in milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of body weight per minute), the easier it is to climb stairs, chase your kids, or power through a workout without feeling gassed. Simply put, a higher VO₂ max means stronger heart-lung performance and greater overall stamina.

Despite its clinical importance, VO₂ max still evokes images of Olympic-level training environments–and that perception creates a paradox. By treating it as a performance metric for the athletic elite, we’ve overlooked its broader role as one of the most upstream, modifiable predictors of chronic disease. In reality, VO₂ max is strongly correlated with healthspan, cardiovascular risk, and all-cause mortality. Yet because it feels out of reach or irrelevant to the average person, we’ve failed to prioritize access to it. It’s a blind spot hiding in plain sight.

Every day that goes by unchecked, the more difficult it becomes to address. VO₂ max decreases by roughly 10% per decade after age 30, unless actively mitigated through training. This means a 40-year-old who doesn’t train aerobically could see a ~10% lower VO₂ max than they had at 30—and by 60, that drop could be closer to 30%. Catching low cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) in your 30s or 40s, when interventions are easier and more effective, could help prevent or delay chronic disease onset (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, cognitive decline).

The impact of VO₂ max on long-term health outcomes is both profound and quantifiable. A landmark study from the Cleveland Clinic—spanning 122,007 adults and over 1.1 million person-years—demonstrated a powerful, stepwise reduction in all-cause mortality across cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) percentiles. Moving from the lowest quartile (<25th percentile) to just below average (25th–49th percentile) cuts mortality risk by approximately 50%. Reaching the above-average range (50th–74th percentile) lowers risk by around 70% (!) compared to the bottom group. To put it in perspective, the effect size of improving VO₂ max rivals or even exceeds that of quitting smoking, managing blood sugar, or treating heart disease. And critically, one doesn't need elite numbers—just reaching the middle third can yield meaningful benefits.

While the science is clear, access remains the primary barrier. The perception that VO₂ max is only relevant for elite athletes is closely tied to the reality that accurate measurement still requires specialized hardware and clinical testing, creating both a mindset and equipment gating problem. True VO₂ max still requires a CPET cart or VO₂ Master-type mask, a trained tech, and maximal exertion. And the requirement for maximal exertion adds an additional layer of physiologic gating. Frail, obese, or mobility-limited patients can’t hit volitional exhaustion safely. This highlights an unmet need for inexpensive, truly accurate submaximal protocols or blood assays integrated into routine panels.

A common piece of feedback we hear is that devices like the Apple Watch, Whoop, or Garmin already estimate VO₂ max. But in practice, these are often little more than wearable illusions. The optical heart rate algorithms they rely on can fluctuate by as much as ±10–20 mL/kg/min. Anecdotally, my Garmin Forerunner underestimated my VO₂ max by 17.5 units compared to the clinically validated CPET test I took through our portfolio company, Eternal.

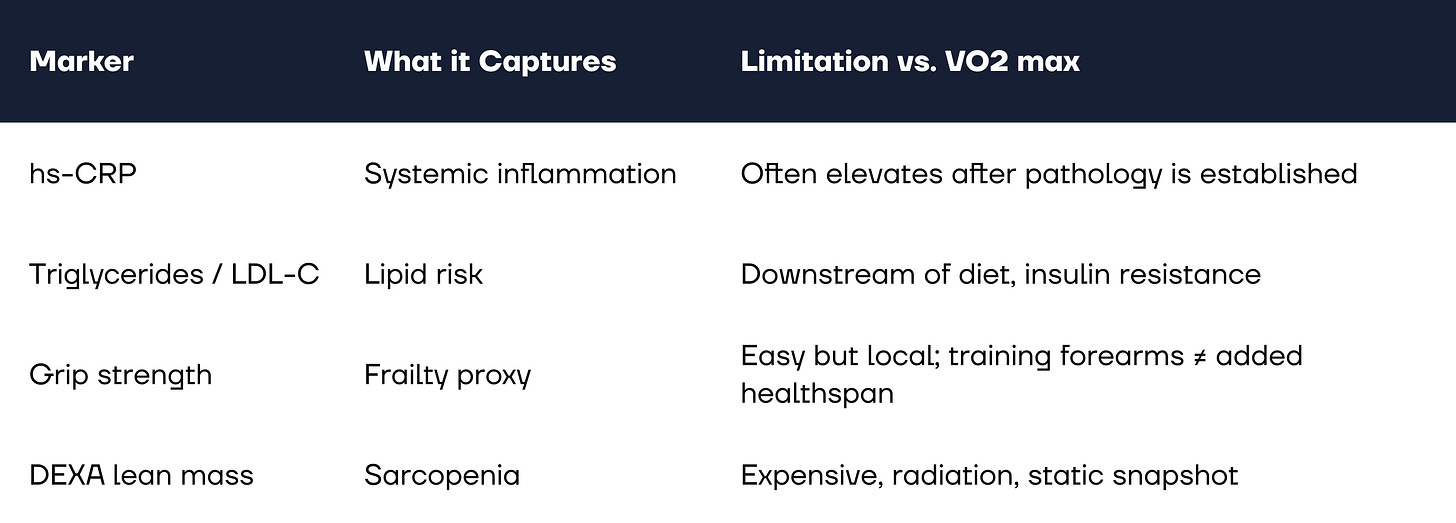

Another common and valid question we receive is how incrementally impactful VO₂ max truly is compared to long-standing clinical biomarkers like C-reactive protein (CRP), triglycerides, or LDL cholesterol, as well as functional measures like grip strength or DEXA-derived lean mass. While being out of range on any of these markers indicates a breakdown in lifestyle or health, we’d argue that VO₂ max is the most upstream, and arguably most modifiable, biomarker we can track.

What sets VO₂ max apart is its predictive and preventive power. Declines in cardiorespiratory fitness often surface years before inflammatory markers like CRP begin to rise, giving it a longer lead time for intervention. In that example, CRP is the smoke and VO₂ max is the dry forest that’s gone without rain for months. It reflects systemic efficiency across the pulmonary, cardiac, vascular, and muscular systems, making it a uniquely integrative and early warning signal for healthspan and chronic disease risk.

Rebranding VO₂ max may start with something as simple as shifting the nomenclature. Replacing the optimizer-sounding “VO₂ max test” with a more relatable term like “cardiorespiratory age check” could improve consumer perception and engagement. Visual framing matters too—percentile charts modeled after credit scores (e.g., red for low fitness, yellow for average, green for optimal) can help individuals quickly grasp their status and motivate improvement.

On the distribution front, access is beginning to expand. A growing number of retail gyms and longevity-focused clinics are incorporating VO₂ max testing into their offerings. Even more promising, a new generation of startups is innovating on lower-friction models – from submaximal exertion protocols to emerging blood-based assays – bringing the metric within reach of a broader population. Hopefully one day, we’ll view the traditional CPET test as an ancient medical practice—just as Midjourney so fittingly portrayed.

This momentum mirrors the tangible consumer shift from reactive care to proactive health management over the past 6 to 12 months. Platforms like Eternal, Function Health, and Superpower have helped usher in what feels like a benchmarking wave, giving individuals clearer visibility into their own health (i.e., discover what’s broken). What comes next is the protocol wave, focused on how to address those insights (i.e., how to fix it).

Improving VO₂ max doesn’t require elite-level training. It’s about consistent effort: 2 to 3 hours of steady Zone 2 cardio per week, a handful of short Zone 5 intervals, and strength work to support heart function and muscular resilience. Sauna use, which has been shown to mimic some cardiovascular benefits, can also play a complementary role by improving vascular function and recovery.

As this shift unfolds, fitness concepts that offer VO₂ max-friendly programming – such as Barry’s, Tonehouse, The Athletic Clubs, hybrid models like HYROX, and the rising popularity of run clubs – are well positioned to benefit. However, whether this demand proves cyclical or secular has long plagued the fitness & wellness category from an institutional perspective. But in a world increasingly shaped by AI-driven time and income abundance, prevention- and performance-oriented behaviors appear increasingly durable.

We’re excited about a path forward that includes rebranding the metric, leveraging innovation to expand access, and integrating cardiorespiratory fitness as a prescribable protocol in preventive care. If these shifts take hold, we believe meaningful gains in healthspan will follow.

Special thanks to Brooks Leitner and Nick Fragnito for thoughts and ideation around this topic!

If you are building or investing within our whole person health thesis, we’d love to chat! Please reach out to jordan@nextventures.com or head over to our website.